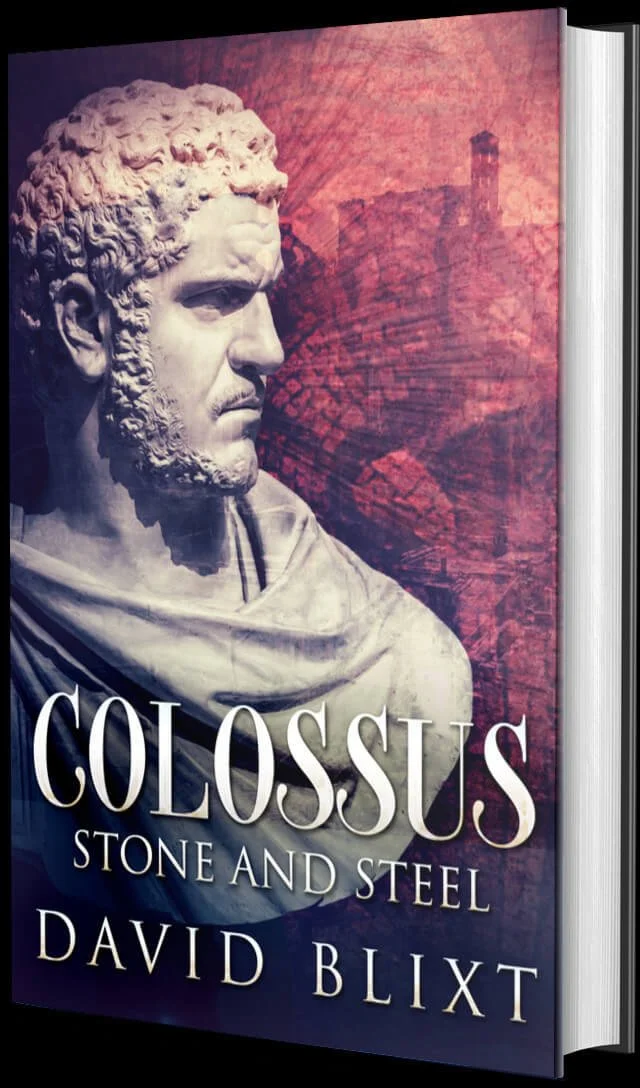

A Historical Fiction Book Series Set In Ancient Rome

Colossus by David Blixt

Series Excerpt

Five weeks after Beth Horon, Judah was hard at work in his father's yard. In his hands he held a great two-headed hammer, heaving it up and shattering stone with thunderous blows. Crack! His handsome face set a fierce grimace, glory and joy all but forgotten. Crack! This was not an age of heroes. Crack! Men achieved greatness through birth, not deeds. Crack! Having played his part, Judah was expected to return to his role as the humble mason. Crack!

And bachelor.

Crack!!

He was striking with far more force than was needed. He imagined the rocks bore the faces of Phannius and Euodias, Deborah's mother, as he smashed them into grit and shards. Damn! Damn! Damn!

He'd waited a whole week after his father's funeral, then gone to the house of Samuel the Mason. Samuel was long dead, as were Phannius' elder siblings. But Phannius' mother was alive and well, the old bitch. Crusty, bitter, bent by a hard life, Euodias was a survivor. One of eleven children, she was the last standing. Sometimes Judah thought that there was not actually blood in her veins, but bile. She thrived on anger and resentment, and all other human emotions were foreign to her. She was as proud of her loutish son as she was jealous of her beautiful daughter.

She'd certainly been in rare form that day. Dressed in his best clothes, washed and with newly pared nails and hair, Judah had arrived with a basket of gifts in his arms. Bread, wine, cheese, salt, and a gift he'd received from the priests – a fine goblet made of crystal, of Syrian design. His sole official reward for his great deed.

But that didn't matter. Deborah was all the reward he needed.

Entering their yard, he'd noted at once it was not as neat as his father's. Saws were left untended, and some bore broken teeth. Chisels lay disregarded. There was such wealth here that they could be careless of their tools. Phannius had seven apprentices working for him, making the House of Samuel far more productive than the House of Matthais. It didn't matter that they turned out less quality stone, or that the joins didn't quite fit. All that mattered was that one drop of noble blood.

To become a priest, one had to prove he could trace his male lineage back to Aaron, brother of Mosheh the Lawgiver, who was the first Kohen Gadol. If a man could do that, he had a leg up on the rest of the Hebrew world. If he chose not to be a priest – there were several thousand priests in Jerusalem alone, tending all sorts of business for the state – a man could carry that advantage into life, no matter his trade or profession. Hence the difference between Phannius and Judah.

Phannius had greeted him coolly. He couldn't be hostile, not after the eagle – and not after the death of Judah's father. But he knew all too well why Judah was here, and clearly didn't approve.

After they embraced, Judah offered his gifts. Phannius was bemused. “Offer them to mother, not me.”

Judah frowned. Phannius was the man of the house. If he was passing the responsibility of accepting the gifts to his mother, it was a bad sign.

But Judah kept a confident smile on his face. He'd talked with Deborah at the funeral, and they had agreed that there was no way he could be refused this time. So when he entered the house and saw the widow Euodias sitting on her hard stool, hunched and crabbed as always, he made an effusive greeting and presented her with the gifts. He kept his eyes firmly off Deborah, seated beside her mother.

The woman could hardly be more than fifty-five. But she looked so old, like a grape that had soured early. Old even when she was young, an age of the soul.

Euodias examined his gifts, not noticing anything but the crystal goblet. That she ran her fingers over a few times, looking for flaws. Finding none, she set it aside. “So, boy. You're a hero, now, are you?” Euodias looked over Judah from heel to head. “They don't make heroes the way they used to.”

Judah couldn't be wounded by the widow's venom, not today. “I came, lady, to ask—”

The woman cut him off with a click of her tongue. “Tch. I know why you came. Like a dog to vomit, you're here to lap up your prize. Well, we can't deny you now, can we? You're a hero!”

Judah didn't know how to handle her sarcasm. “I don't claim to be a hero.”

“Nor should you!” Her voice had the dark edge of a blood-stained knife. “My son told me all about it! How you left him to defend himself while you leapt after the eagle! How he kept the Romans off your back as you stole the eagle, then raced to safety. A pity you were too stingy to share any of the credit with those good men who kept you alive. They're the real heroes!”

Judah turned to stare at Phannius. The lout didn't even have the good grace to look embarrassed by his lie. They both knew he'd been nowhere near the eagle when Judah took it. It had been Levi who had protected Judah's back. But Phannius' face was set in a mulish expression, as if daring Judah to make him look bad in front of his mother.

Judah blew air out his nose like an animal, but knew the truth wouldn't help his cause. Carefully, he said, “Lady Euodias, no one has asked me for an account of the events. I agree that the man who defended my back should have all the honour due him. And I would be happy to share the credit with your son, or whomever you please.”

“Oh? Magnanimous, isn't he? Already trying to act better than his place. As if he wasn't some jumped up son of a labourer. Just like his brother, ideas above his station—”

“Mother…” said Deborah softly, her lips pinched tight.

“Quiet, girl! I suppose you think that we should pity him, having lost his brother and father. I could have told you that the brother would come to no good. As for Matthais – imagine, being felled by the loss of a son. Tch. I've lost three, including the best of them, and I'm still upright. But men are made of weaker stuff…”

The inference that Phannius was not her best son didn't seem to affect the big man, he'd heard it so often. Judah almost felt sorry for the lout. At least he understood why Phannius had told his lie. No doubt she had flayed him for not bringing the eagle back himself.

It was clear she had no intention of granting permission for Judah and Deborah to marry. Technically, of course, that refusal should have come from Phannius, the senior man in the household. But there was no doubt as to who ruled here.

Still, Judah wasn't about to slink away like a whipped cur, his tail between his legs. He would make her say it. “Lady Euodias. I have come to humbly ask your permission to take your daughter's hand in marriage.”

Tears stood in Deborah's eyes. She didn't look at her mother, but tried to convey as much as possible before he was made to leave.

Euodias let the moment drag out as long as possible. Then she jerked her chin at her son. “Phannius is the man of the house. You should be asking him. Insulting! Imagine, asking an old woman's permission when he's standing right there. First you keep him from his just desserts, then you heap scorn upon him by placing a woman over him. Or worse, acting like he doesn't even exist!” She looked to her son. “And what kind of man are you, that you let him treat you so? Are you afraid of him? He always was a bully, even as a boy. Well, Judah ben Matthais, you can't have your little prize. Stupid as she is, she is comely – almost as pretty as I was at her age. She's made for a better husband than a common mason – even a hero! Her maidenhead will go to a wealthy man of the Lower City, maybe even the Upper. But don't worry, hero, you won't have to see it. We won't want common folk at the wedding. Come, Deborah!” She took her daughter's hand and physically led Deborah deeper into the house. She took the goblet with her.

That left Judah alone with Phannius. Judah wanted to say something insulting, but decided that the best thing to do was to treat him just as his mother had described. Ignoring him completely, Judah left the house with his head held high.

He didn't remember the walk home, and the weeks since seemed a blur. Work, work was the answer. He pushed his body past enduring, taking up the worst physical labour he could find, straining so hard he tore open the scabs from the battle and bled afresh.

Fortunately there were many orders to fill, mostly from the priests wishing to fortify the city walls. Priests. But Judah swallowed his anger and worked from dawn till dusk. When he fell into his bed each night – alone – he had to be too tired to think. Because thinking made it worse. In his unworthier moments he wished he'd succumbed and bedded Deborah the night after the battle. Euodias would have had to agree, or else complain to the priests that the hero of Beth Horon had deflowered her daughter. But Judah didn't wish that kind of shame on Deborah. And on the night his father had died…? Everything conspired against them.

Among the neighbourhood, the refusal reflected poorly on everyone. Deborah's family had denied her to the hero of Beth Horon. But some said they must have had reason. People began looking at Judah as an upstart crow, a man with ideas above his station. The luster of his great victory was a little tarnished. Not that Judah cared. He threw himself into work, imagining each hammer-fall a blow against his enemies.

His other respite was his new friend, Levi. The gaunt and bearded bodyguard appeared one day in the yard, a mocking smile on his lips. “So this is where you learned to fight. Pity you didn't have that hammer at Beth Horon.”

“We did well enough without it.” Judah dropped the hammer to embrace the taller man. Seen in normal circumstances, not covered in dust and blood, Levi ben Patroclus looked to be in his middle thirties, though the shaved head made him seem older. His skin was weathered, too, aging him further. Judah couldn't say what the original hue had been, but the man had some northern features – a slightly wider nose that flared when he talked, a jutting chin under his neat square beard. The massive sword hung in a baldric upon his back, too long to be carried at the waist.

“Thank you,” said Judah when they were sipping water and lemons in the house. It wasn't empty anymore. He'd kept his word to his dead friend and taken in Jocha's widow and son. The woman kept house for him, and the boy earned their keep as his third apprentice. It was the widow, close to Levi's age, who brought them the fruit drink, and then returned with small wafers frosted with sugar. She smiled at Levi, who thanked her, then said to Judah, “As for your thanks, hothead, I'll do without them. You thanked me once, which was more than was required. Thank me again and I'll make you eat that rock in the yard.”

“I'd enjoy seeing you try. Though I suppose if I had to have just one man protecting my back, I'm glad it was a bodyguard.” He paused, then said, “I feel bad. You lost your position because of me.”

“No. Because of me.”

“I never asked who you were guarding. Some priest?”

“No,” replied Levi, swirling the cup in his hand. There was a patina of dust floating on the surface – everything in the house was inevitably covered in grit from the yard. “I was the bodyguard for King Agrippa.”

Judah choked on his drink and Levi grinned. For a moment Judah didn't know whether to believe him or no. Then he started laughing and invited him to supper.

They supped together three more times in the last two weeks, and Levi kept Judah informed as to the course of the war. “Not that there's much to tell, yet. The murders have ended on all sides – no one left within reach to kill. Now everyone waits to see what Nero Caesar will say.”

“Is there any doubt?”

Jocha's widow, Shalva, had made them a thick stew this time. Her cooking inexplicably improved whenever she knew Levi was coming.

Picking out a hunk of lamb meat and lifting it to his lips, Levi shrugged. “From what I heard the king say, one never can tell with Nero. He thinks he's an artist. He might just compose us a ballad and let it go.”

Judah pulled a face. “You don't believe that.”

“No,” agreed Levi. “I don't.”

Praesent id libero id metus varius consectetur ac eget diam. Nulla felis nunc, consequat laoreet lacus id.