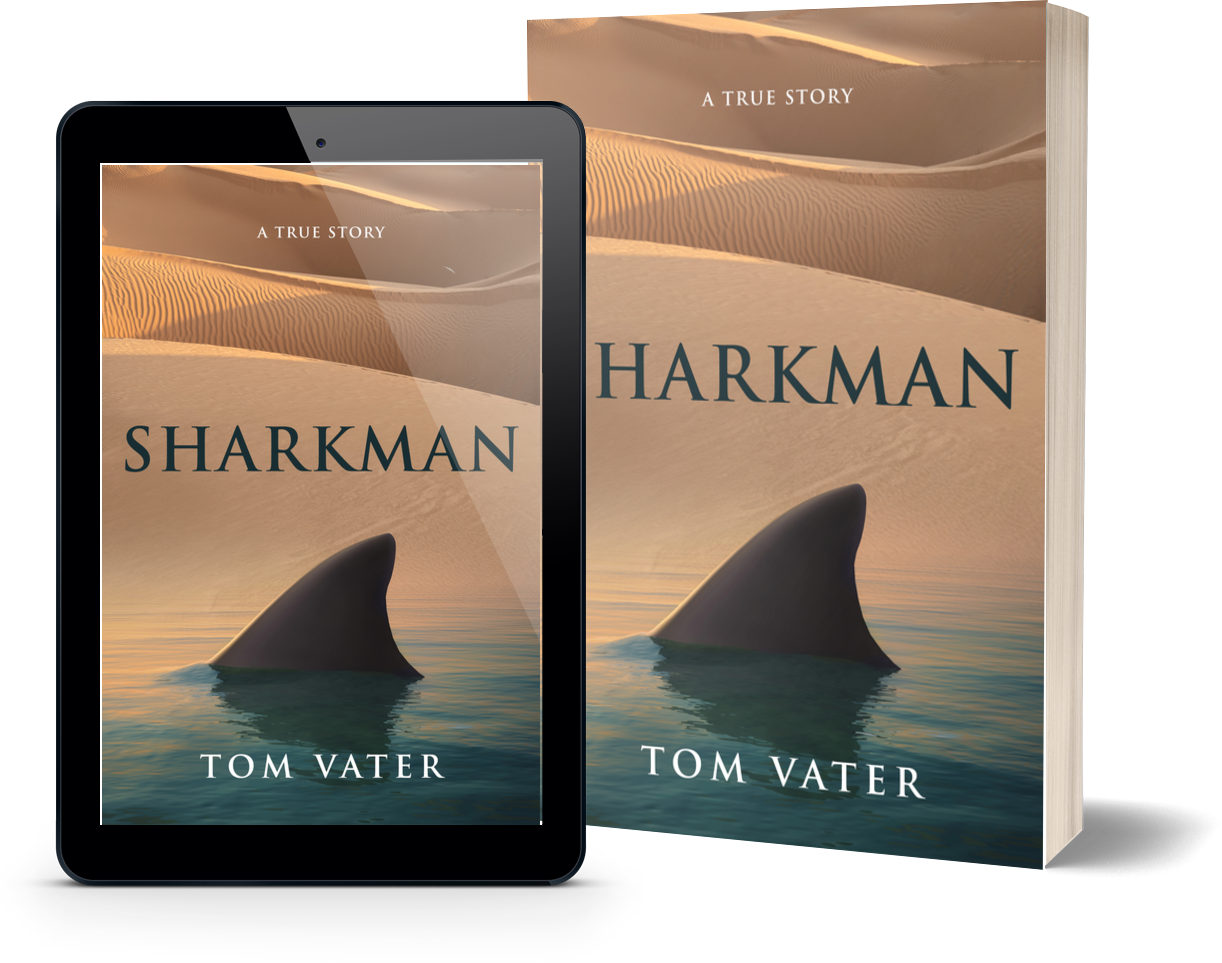

Sharkman

Book summary

Three young adventurers set off from Germany to cross the Sahara in 1992, only to be kidnapped by bandits and vanish. Thirty years later, one of them, Peter Hauser, lives in Thailand and swims with tiger sharks, exploring the depths of human fear. SHARKMAN is a gripping tale of survival and self-discovery.

Excerpt from Sharkman

Peter Hauser is a happy man. He’s lying in his hammock, a cold can of Leo in his right hand, a joint in his left, his lanky frame exhausted after spending the day floating above the coral reefs of the Koh Surin archipelago, his wry smile sliding a little closer to the sand as inebriation sets in. The tide is up, lapping at the powdery sand of Mai Ngam Bay, almost reaching up to his tent at the edge of the jungle. There’s phosphorescence in the water, silver glitter cresting the low waves. Giant fruit bats circle overhead. Lizards scuttle in the undergrowth. Out, beyond the waves, the house reef is teeming with silent life. And death.

Ever since he was a teenager, Peter has been getting Fernweh, something akin to and yet more than wanderlust, the longing to be elsewhere. Most winters, he heads out to Thailand, to Koh Surin, to Mai Ngam Bay, where he spends three months, sleeping on a thin mattress in a small tent, fronting evergreen forest, facing the ocean. This three-hundred-metre sand crescent is framed by two sheer hillsides covered in dense rainforest. Eagles take off and land in the dense canopy. The vibe is almost pre-historic. Mai Ngam Bay is in Moo Ko Surin Marine National Park, a special, far corner of the world, home to sea nomads and an astounding variety of ocean life.

Peter doesn’t come to Thailand to go sight-seeing, to get a tan or to find a girlfriend. Peter is here to swim with sharks. Out in the blue of the Andaman Sea, the truly fearless, or the truly mad, snorkel with tiger sharks, apex predators more than four metres long, that patrol the channels between the national park’s jungle-covered islands.

Peter, tall, broad-shouldered and gangly, blessed with George Clooney movie star looks, more lust for life than Iggy Pop and a disarming smile, laughs at his fortitude, “It's amazing that after what I've experienced in life, everything still works in such a way that I can go swimming with these beautiful animals.”

Peter lives in Kirchheim-Teck, a small town in southwest Germany. He’s been working as a mechanic for Daimler Benz since he was sixteen. Growing up on a housing estate in even smaller-town Wernau, shirking military service, smoking dope, and listening to punk rock, Peter was always one for whom 'normal' life wasn't enough, one who wanted to learn something about his limits, one who wanted to see the world, wanted to talk to people. As if he’d escaped from the pages of the Brothers Grimm, he was ‘the youth who went forth to learn what fear was’.

Peter learned a little more than he’d bargained for.

“It all kicked off exactly thirty years ago today. I was 28 years old. It was my sister's birthday. And my niece’s birthday too, as I found out later. Just thinking about it now makes my hair stand on end. Africa!”

***

Peter, Klaus and Hummi arrived in Bordj Badji Mokhtar, a town of 16,000 souls - the last large settlement before the Algeria - Mali border, on the evening of January 11th, 1992.

The three friends drove battered Peugeot 504s. Peter had a Familial with three rows of seats. Klaus piloted a beautiful golden estate, while Hummi drove an ordinary model. The 504s, solid and strong cars, worked well in the desert.

“These cars were cheap. I paid a thousand marks for mine. They only had value in Africa. Most of these Peugeots became bush taxis. In Togo, they turned old cars into miracles. They cut them up and riveted them back together to make one out of two.”

A jeep sat by the side of the road on the edge of town, riddled with bullet holes. A small convoy of Italians had traveled along the same route a month earlier. They’d tried to flee bandits who had opened fire with a machine gun mounted on their jeep. One of the Italians had died. The shot-up car remained, a gloomy monument to bad luck.

As the German travelers entered the town, children threw stones at them.

They reached the town’s campsite, which looked abandoned and unfriendly, at sunset. They met another group of travelers who had decided to turn around and drive all the way back to Morocco. Hummi too was getting cold feet. He told his friends that he didn't want to cross the border. Peter and Klaus were adamant. As far as they were concerned, there was no turning back.

“We had everything. We bought pallets of beer at Penny Mart. We had canned food. We had rice, noodles, and onions. We had milk, oatmeal, muesli, and coffee with us. We bought a large ham in Spain. Klaus had a pull-out gas cooker. Each car carried 200 liters of fuel and 120 liters of water. In addition, we carried spare parts and tools. And we had good Michelin maps. There was more on those than there is on Google Earth today. We were well prepared. And I didn’t want to drive back.”

They cooked and had a few beers, Peter and Klaus talking at Hummi. Heading back to the alternative and presumably safer Hoggar Route was too far, they didn’t have enough petrol. There was just enough fuel to get back to the Moroccan border, and what would they do there? They had sold almost all their clothes. Peter was determined to sell his car in Africa.

As they sat talking, a woman appeared out of the night, covered in yellow powder. Her hair stuck together like clay. Nobody on the campsite wanted to talk to her. Other campers told her to get lost. She looked ageless. Perhaps she had once been beautiful, but now she looked emaciated and sad. Peter and his friends didn’t mind her and she sat down with them and started giggling to herself while stacking their spent beer cans on top of one another, knocking them over and starting all over again. They offered her food and drink. She refused.

Hummi told his friends that he’d prefer to sell the car in Germany.

“I told Hummi that the cars were worthless back home, and by now, no longer legal. Klaus and I were totally positive, and I knew the route. We buried some money in Bordj Badji Mokhtar, to have something to fall back on in an emergency. And if anything happened, we'd just step on the gas. We pressured Hummi into acceptance and went to sleep.”

The mud-caked yellow woman returned early in the morning of January 12th, with three carnations in her hand. She gave the flowers to the three travelers. How had she managed to conjure up three carnations in the desert?

“The flower of death,” Hummi remarked.

The woman left with a lopsided smile, whispering incantations to herself. Peter and his friends broke up camp and headed to the police station. The immigration officers demanded to see the money they had declared upon entry into Algeria and the cars’ papers.

The border guards checked the cars’ chassis numbers against their documents. A rhombus had been carved in front of the chassis numbers on all three cars. The immigration officers suggested that this looked like a zero. That zero wasn’t on their papers. Despite their protests, the officers told the travelers that they would have to wait for the boss to pass judgement.

They waited all day.

The chief of immigration showed up as the sun set and decided, in barely a minute, that their papers were in order. He put the necessary stamps into their documents.

They were free to go.

Peter and his companions decided to head back to the campsite for another night’s sleep, but the border guards insisted that now that they had their exit stamps, they needed to leave Algeria immediately.

Bordj Badji Mokhtar lies less than a hundred kilometres north of the border. They got into their cars and drove into the night. There was no formal border demarcation, no fence, no border post, nothing. A few kilometres into Mali, a giant white sign loomed by the side of the road which informed them that they’d entered the country. Half-buried coils of barbed wire left over from the French-Algerian war still littered the Sahara and were invisible after dark. They were too scared to continue.

On both sides of the sign, low plateaus rose from the desert. They made camp in the shadow of one of these knolls, parked their cars in a triangle and cooked dinner. Peter told Klaus and Hummi that it was his sister’s birthday and that she was also heavily pregnant and was perhaps giving birth to his niece that night. Everyone was a little nervous and Klaus stashed his cash in a film box and put it under one of the wheels of his car. They had a few beers and went to sleep early, as they wanted to get going at the crack of dawn.

***

In the 1960s, young adventurers traveled from London to Kathmandu. The route became known as the hippie trail. These counter-culture pioneers, disillusioned with the burgeoning consumer lifestyle back home, traveled on shoestring budgets. They were hungry for self-realization, drugs and the exotic. Following the revolution in Iran and the resultant closure of the Asia overland route, the road from Europe through West Africa to Togo became the classic post-hippie road trip alternative of the 1980s. Hundreds of young Westerners drove old cars across the Sahara. Many made it all the way to Togo’s capital Lomé where they sold what was left of their sunburnt, tormented vehicles. There were two routes, through Morocco to Algeria, and to Togo: The 1000-mile Tanezrouft route into Mali, and the shorter but more dangerous Hoggar route through Niger. The last leg of both routes, through Burkina Faso and into Togo was the same. The Hoggar route was known for bandit attacks and travelers drove in convoys with military protection. Peter and his friends chose the Tanezrouft route, which Peter knew. That route was said to still be negotiable by individual travelers.

Only the Tuareg, nomadic Berber tribesmen whose clans live across Algeria, Mali, Niger, Libya, Nigeria and Burkina Faso, survive in the desert. Legends trace the community back to Tin Hinan, a queen referred to as ‘the mother of us all’, who lived in the 4th century AD. They call themselves Imuschag (the free) or Kel Tagelmust (people of the veil) as their faces are always wrapped in blue indigo scarves.

Following the demise of the French colonies, the Tuareg’s movements were curtailed by newly emerging nation states and there’s been intermittent armed and bloody resistance against dominating governments ever since.

Tanezrouft, long known as the Land of Thirst by the Tuareg, is one of the most desolate, featureless parts of the Sahara, most of it located in Algeria. The first traverse by car succeeded in 1922. There’s little vegetation. There are no landmarks. The arid, dry landscape is shaped by the wind. In the summer, temperatures rise to 52 degrees Celsius.

Praesent id libero id metus varius consectetur ac eget diam. Nulla felis nunc, consequat laoreet lacus id.