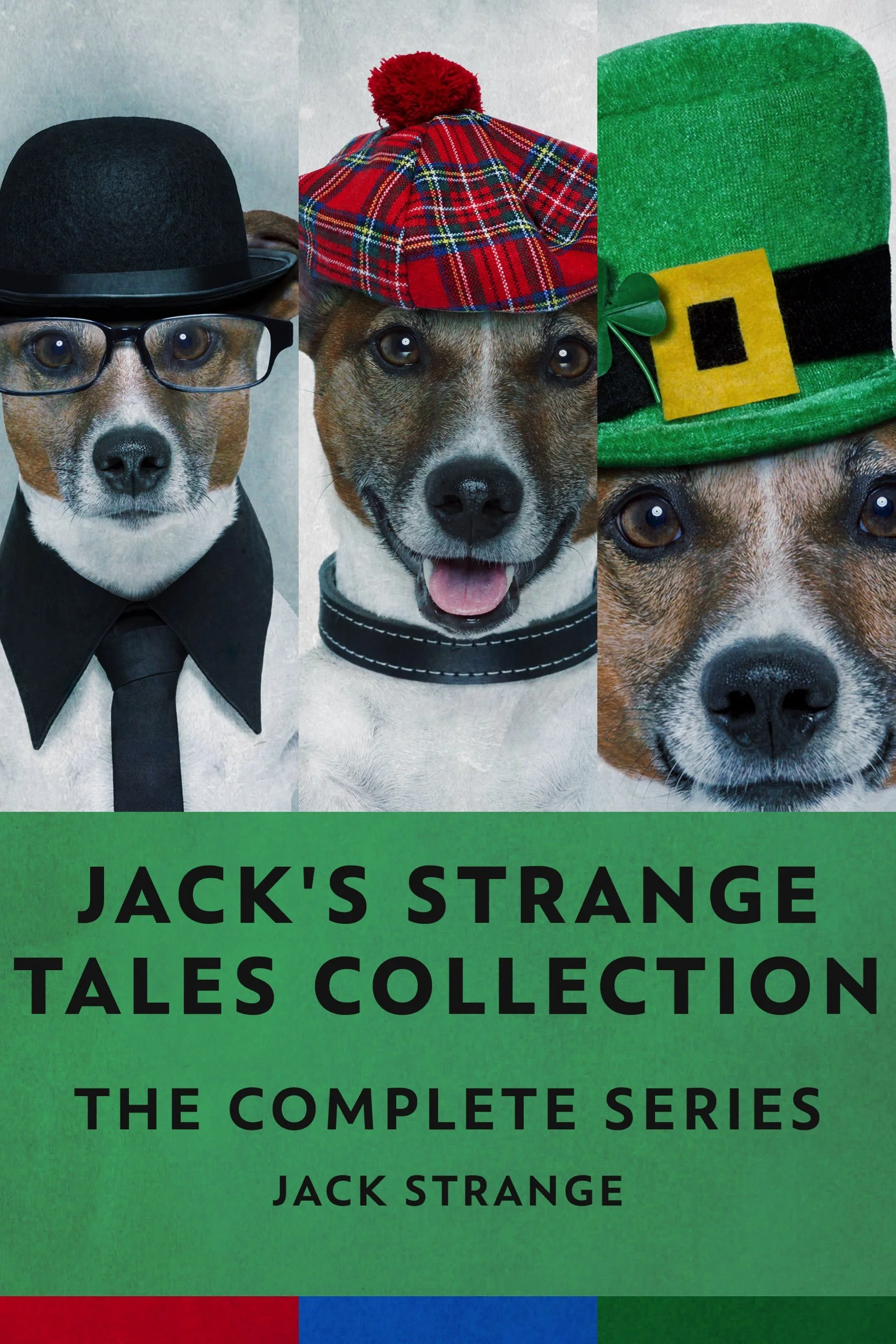

Jack's Strange Tales Collection: The Complete Series

Excerpt from Jack's Strange Tales Collection

Haunted Ships

Ships, like houses, may be haunted, but while it is relatively easy to walk out of a haunted house, it is much more difficult to leave a haunted ship at sea. Perhaps for that reason, supposedly supernatural happenings on board a ship often appear more threatening than the land-based variety. Strangely, seaborne ghosts do not appear to have any time period; vessels of the twentieth century appear to have been as susceptible to haunting as those of the eighteenth or nineteenth, yet some of the more memorable stories appear from the Victorian era. Perhaps the Victorian cult of the dead and liking for Gothic romance may be blamed.

In April 1874 the ship Harewood, homeward bound from Pensacola in Florida arrived at the Tail of the Bank, just downstream from Glasgow in Scotland. Some of the crew appeared in an agitated state, and soon the stories were circulating around the bars of the Broomielaw. The local press soon heard rumours that Harewood was haunted and a reporter began asking questions of the crew. One man, who had shipped aboard as an A. B. (Able-bodied seaman) gave his version of events. He said that after a few days he noticed that the hands were collecting in small groups, talking about the strange sounds that they had heard. He also mentioned hearing stories that the ship had once been named Victoria of London, and that there had been a murder on board.

Many seamen believed that it was bad luck to change the name of a ship, for such a procedure often brought bad luck. For instance when the owners of the German four masted barque Rene Rickmers changed her name to Aland, she was lost at New Caledonia on her very next voyage. It was not wise to tamper with such things, so there would be some superstitious fear about putting to sea in Harewood. That fear would be augmented with rumours of a murder. The seaman said that, although he worked as hard as ever, he found it hard to sleep, and he often heard the sounds of groaning, as if somebody was 'in deep distress.' One morning, he said, he awoke around dawn to see 'a figure standing' by his bunk. 'It was that of a young man, apparently about 27 years of age.' The seamen knew at once that the figure was not human; he also knew that it was a 'foreigner' but would not hurt him.

The figure stared at the seaman before it retreated 'into a corner and pointed to a livid mark round the neck.' All the time the figure's lips were moving 'as if in prayer.' After that the seaman frequently saw the figure, who spoke the same words again and again;

'I am not the man. I am not the man.'

It seemed that an elderly banker had been murdered on board Victoria of London and a man named Miller had been hanged for the crime. The seaman believed that this figure, which was seen 'gliding along the deck', on dark nights, but giving out 'a sort of phosphorescent light' was the ghost of the executed Miller, come to protest his innocence. 'I would not sail in that ship again for worlds' was the seaman's last word on the matter.

Sometimes the ghost on a vessel was known personally to the crew. It was common for a ghost to be a seaman who had once served on that vessel, but who had drowned, or been killed in some shipboard accident. This spectral mariner could lend his weight on a line when needed, or give advice during a storm. It was less common for the ghost to be unfriendly, although sometimes the crew would believe their extra hand to be the devil, complete with forked tail, cloven hooves and a smell of brimstone.

John Masefield the maritime poet mentioned a ghost on John Elder, a vessel built in Glasgow in 1870 for the Pacific Steam Navigation Company. According to Masefield, who probably heard from a crew member, the poop of John Elder was haunted, although the ship seemed to suffer no ill effects from the spirit. Discovery, who sits at Riverside in Dundee, is reputedly haunted. The light bulb above a bunk used by Ernest Shackleton blew without reason, and it is said he stalks the ship that he loved, but others think the ghost is of a seaman named Charles Bonner who fell from aloft in 1901.

In the early twentieth century British trawlers regularly travelled to fish in Icelandic waters. These were steam trawlers, with funnels so thin that they were known as 'woodbines' after the popular brand of cigarettes. Life on board these vessels was not comfortable, with the men berthed right forward, where the pitch and roll of the vessel could most easily be felt, and the skipper and mate right aft. In every kind of weather, the crew worked on an uncovered deck, gutting the fish, playing out the net, all in the teeth of wind that carried ice straight from the Arctic. The firemen had an equally harrowing time for they worked within a tiny space, shovelling coal into the boiler despite the frantic movement of the boat. They also had to clamber up on deck to dump the ashes, moving from extreme heat to sub-zero cold within the space of a minute. On one occasion a fireman was on deck when a massive wave broke over the vessel, sweeping him to his death. Yet something of him remained on board. His comrades often saw him working in the bunker, and whenever they came near to his berth, a ghostly voice sounded the warning, 'don't touch my bacca!' Although they had known him as a friend, other members of the crew refused to enter the bunker for the remainder of that voyage.

Large liners could also be haunted. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the most prestigious liners had four funnels but when Titanic was built, her fourth funnel was false, purely for effect. Before her maiden and final voyage some of the crowd saw an engineer inside this funnel, where no man ought to be. Some said that such an apparition was a bad omen. Another passenger steamer was blessed with an extra steward, who was seen gliding through the dining rooms. Legend speaks of the ghosts on the passenger liner Utopia. She was on her outward voyage from Italy and calling at Gibraltar when she collided with HMS Anson. As soon as Utopia began to go down, vessels and boats of all sizes arrived to help take off the passengers and crew, but many were still on board when she sank.

Utopia's owners could not afford to lose such a valuable ship, so had her salvaged, and she was towed into the dockyard at Gibraltar and refitted. As soon as it was practical, she returned to her previous work carrying passengers on cruises and trips. However, things were not all well. Passengers began to complain about strange sounds on board, and every time Utopia passed Gibraltar Bay passengers and crew experienced the sinking. They heard the sounds of rushing water and the cries and screams of people drowning. Not surprisingly, the stories spread, and fewer passengers used the ship. The owners even found it difficult to find crew, so eventually Utopia was sent to the breaker's yard. The ghosts had won the day.

Sometimes, however, the ghost met its match in a courageous officer of the watch. Norfolk was a Blackwall built ship, used for long haul passages from Britain. On one such voyage, she met dirty weather off Cape Horn and hove to until the weather moderated. While the Cape Horn snorter threw forty foot greybeards at them and every member of the crew working flat out to keep the ship afloat, nobody had time to worry about ghosts. However, as soon as the wind eased, some men heard an unusual noise. Not even the experienced Boatswain knew what it was, but one man likened it to the 'rattle in a dying man's throat.'

Superstitious as some seamen could be, the crew were far more unnerved with the unknown sound that they had been by the gale, and they began to see things that were not these. The atmosphere on Norfolk changed, so that when somebody began to scream during a night watch, men looked at each other in fear.

Praesent id libero id metus varius consectetur ac eget diam. Nulla felis nunc, consequat laoreet lacus id.