Survival and Revenge: The Dark Alchemy of Power in the East End

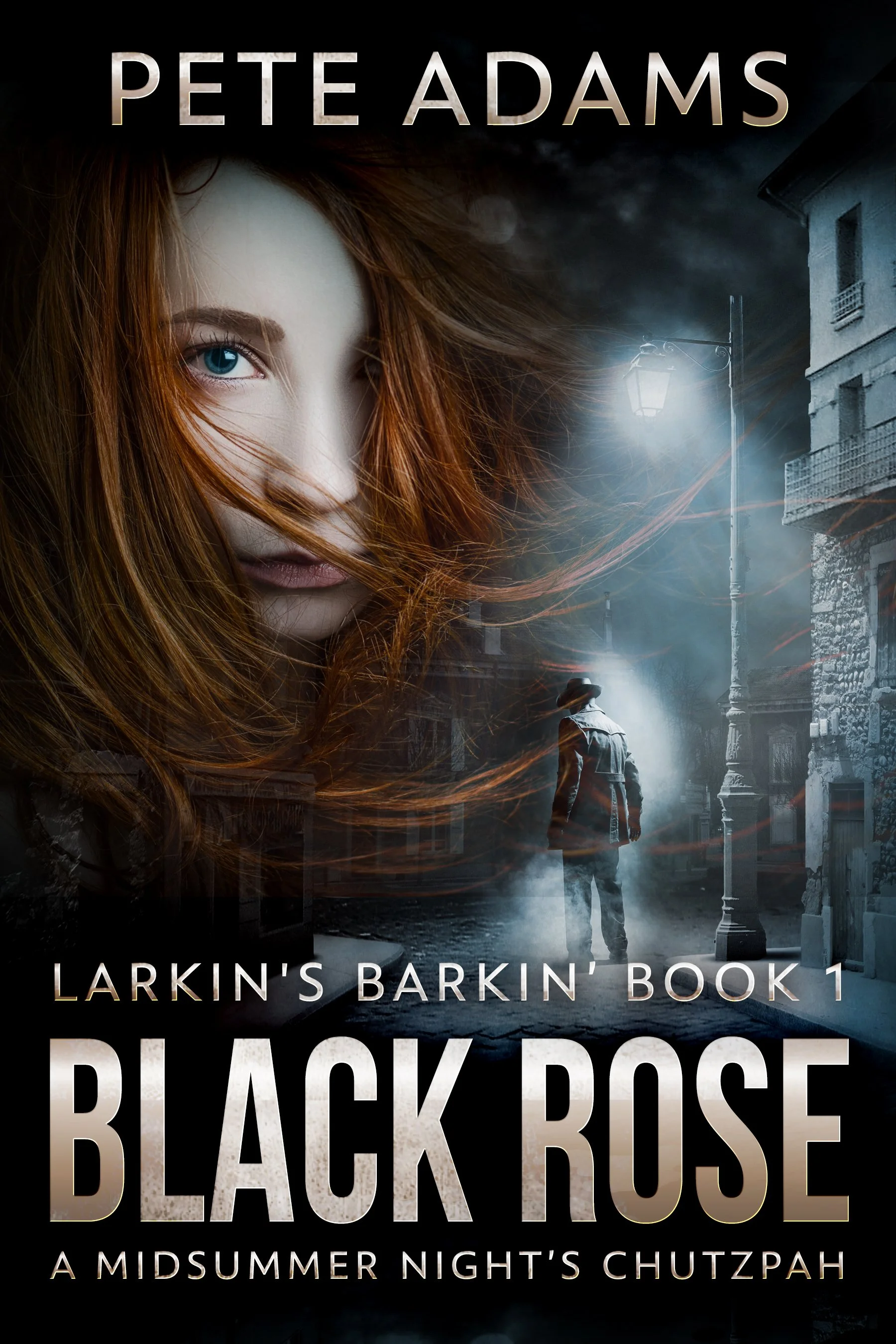

In the brutal world of London’s postwar East End, survival is less an instinct than an art form. Beneath the smog and the noise, the city’s broken streets conceal an ancient theatre of dominance, superstition, and fate. Pete Adams’s Black Rose blooms in that darkness, where a boy once bullied into silence learns that to survive is to transform — and transformation, in such a world, comes at a terrible cost.

Chas Larkin’s evolution from a victim of cruelty to a young man capable of reshaping the underworld is more than a revenge narrative; it’s a meditation on how trauma breeds resilience. The slums of 1960s London, still scarred from bombs and poverty, become a crucible in which Chas’s anger is forged into something potent and dangerous. Guided — or perhaps haunted — by the enigmatic figure of Roisin Dubh, the Black Rose, he channels his pain into purpose. The gangs, the IRA, even the secretive machinations of MI5 — all become instruments in a larger symphony of vengeance and survival.

At the heart of this story lies a question of inheritance. Chas does not only inherit the violence of his environment; he inherits its codes of loyalty, power, and retribution. The matriarchal presence that threads through Black Rose — embodied by women who endure, manipulate, and mend — adds a haunting counterpoint to the masculine world of fists and fire. These women, from detectives to healers, are the quiet architects of endurance. In their shadowed strength, Adams weaves a vision of the East End where salvation is not found in mercy, but in control — and where every act of compassion is tinged with blood.

Revenge in Black Rose is never simple. It is theatrical, cyclical, and strangely mythic. The recurring whispers — The O’Neill’s say Hi — echo through the story like an incantation, blurring the lines between human vendetta and supernatural omen. Superstition and political intrigue intermingle, suggesting that even the most personal acts of violence are part of something larger: the city’s own restless hunger. As Chas ascends, combining the power of warring families under his rule, he becomes not only a survivor but a symbol — the embodiment of a community that has learned to wear its wounds as armour.

Pete Adams, known for blending dark humour with moral complexity, crafts in Black Rose a world where justice and vengeance share the same face. His East End is not simply a setting; it is a living, breathing entity — both victim and perpetrator of its own history. And in the flicker of its broken lights, Chas Larkin’s story reminds us that survival is never pure. It is always, in some measure, a dance with the shadows that shaped us.

Praesent id libero id metus varius consectetur ac eget diam. Nulla felis nunc, consequat laoreet lacus id.