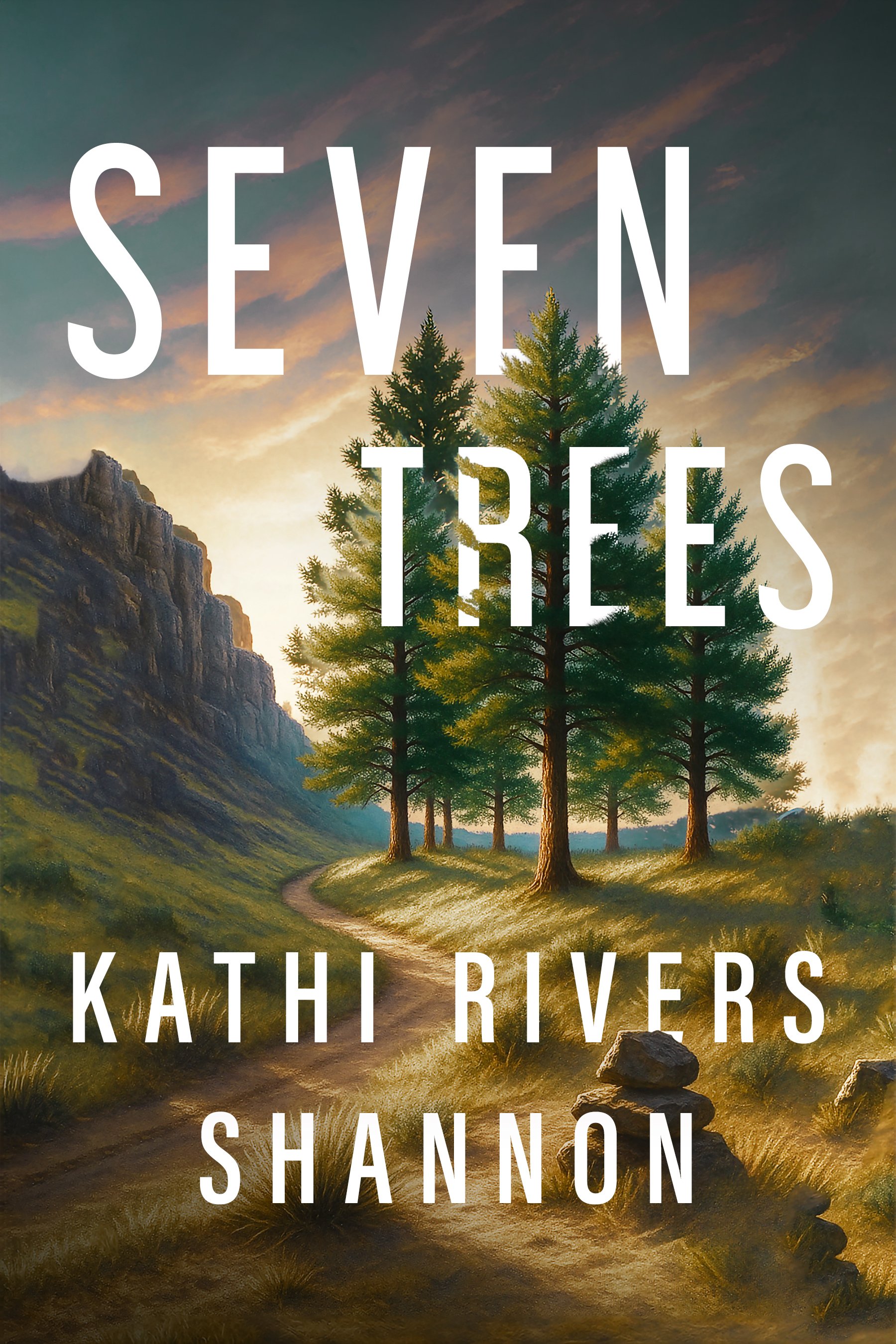

Seven Trees

A stranger at the door. A country on the edge. A summer that changes everything.

In Seven Trees, nineteen-year-old Annie Burgh is doing her best to keep her small-town newspaper running as the Vietnam War divides the country—and her own community. When a draft dodger named John shows up with her editorial in hand, asking for help to escape to Canada, Annie agrees. But the deeper she goes, the more she realizes John isn't exactly who he claims to be.

As Annie hides him in the remote canyon homestead of her ancestors, long-buried secrets of her own family's past begin to surface: a mysterious death, an abandoned grave, and a diary that holds both personal and political revelations. Over five intense days, Annie confronts who she is, what she believes, and how far she’s willing to go for conviction, love, and family.

Set in the summer of 1970, Seven Trees is a haunting coming-of-age novel from Kathi Rivers Shannon, blending historical fiction with suspense, memory, and the enduring question of what it means to do the right thing.

Get your copy of Seven Trees and step into a story where every truth has its cost.

Excerpt from the book

My mind couldn’t shake either of those images that summer. Vietnam and the wolf. The wolf and Vietnam. It didn’t matter which popped into my mind first—the other would soon follow. Perhaps it was because the day of the wolf was the same day my boyfriend Rick told me he’d enlisted in the Army, the day that prompted my editorial and brought the stranger, John, into my life. Even today, Vietnam and the wolf meld together, inseparable. Together, they were the start of an unraveling, a shifting, a breaking-apart.

Rick told me of his betrayal in the drugstore before I could tell him about the spook light. He’d enlisted without asking if this rearrangement of our lives was okay with me, as if I’d scramble to keep the oneness of us whole. Did My Lai mean nothing? Did he think Vietnam was just “blowin’ in the wind?”

Did he think he couldn’t die?

Would he—could he—kill a baby?

The whine of a milkshake mixer faded like a dying siren. No one in the drugstore spoke. A truck roared up Main Street. I laid my open notebook on the counter, the settling of the paper as soft and quiet as if it didn’t exist, as if I didn’t exist. I leaned toward my notes from the sheriff’s log, pushing away from Rick’s words. The dispatcher had recorded the time of Ian’s call at 10:21 p.m., April 21, 1970. I read each word separately, unable to string them together, Rick’s announcement hot in my chest. I read the words out loud, as if they still mattered: “The light glowed and hovered like a lantern hung from a barn rafter, shot west across Ian Jenkins’s back wheat field, hooked north. Jenkins dropped his wrench on his foot, circled his hand around for the head of his black lab whimpering at his side, and hollered for his wife.”

Rick, who didn’t believe in spook lights, reached over and closed the notebook. “It’s better than being drafted like Jimmy Palmer,” he said, his voice slipping from a clipped cadence to a pleading tone, the one he used when he tried to get me to sleep with him. He raised his hands to grip my shoulders.

I jerked away. “But we talked about this,” I said. “You agreed. They won’t draft you—you’ll get a student deferment.”

He dropped his arms. “It’ll be better this way,” he said. “You’ll see.”

I looked at Rick’s reflection in the long mirror across from the soda fountain, tried to reach into his thoughts, but it was as if he no longer lived inside himself. I grabbed my notebook and walked toward the door, my steps heavy but my head airy, as if all the blood in my body had sunk into my feet, leaving the rest of me empty, so light a gust of wind could whirl me down Main Street, my bones nothing more than dry, tumbling twigs.

“Annie.”

Without turning around, I brushed my left arm back, palm out, fingers spread, as if I could stop sound, thoughts, anything trailing me.

Praesent id libero id metus varius consectetur ac eget diam. Nulla felis nunc, consequat laoreet lacus id.